“Confronting “the bad guys” is an essential part of an investigation.

Every journalist is bound to, at least once in their career, to call up “the antagonist”, to confront them with what was said about them, ask for clarifications and counter arguments. Many of us dread that moment, and it is sometimes hard to estimate when exactly we should make the dreadful call.

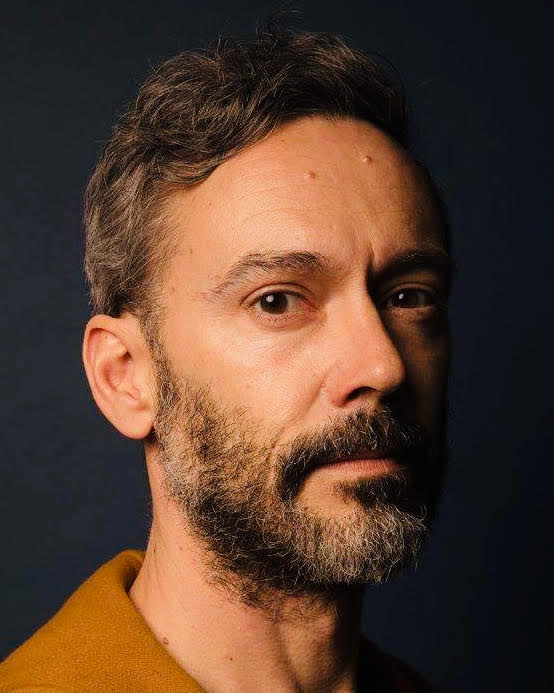

Journalists Margherita Bettoni, Nils Hanson and Micael Pereira who have confronted many “bad guys” in their career, will join us for a session to talk about how and when they decide to confront the subject of their investigation.

If something fills us with anxiety, we might want to postpone it for the very last minute. But veteran investigative journalist Nils Hanson believes this not necessarily a great idea. “This is not something you do dutifully at the last minute. On the contrary, it should be one of the significant parts of an investigation. If you are sincerely searching for the truth, you should ask yourself: How soon can I contact “the other side”? The sooner, the better,” he says. By establishing early contact with the subject of the investigation, you can get explanations and facts you otherwise probably will miss, he believes.

In some investigations, however, that might not be the best idea. Margherita Bettoni who has specialised, among other things, in coverage of the Italian mafia in Germany, stresses that while the confrontation in an early stage might be useful in some cases – in others it might give the “bad guy” precious time to cover his wrongdoing. “While investigating dangerous criminals, it might even be recommendable to confront them just short before publication to avoid safety risks,” she points out.

But the question is not just when, but also how. Portuguese journalist Micael Pereira says that bad guys should be confronted “in a way we can expose the ethical and emotional dilemmas they are involved with.”

“This should be done, ideally, face to face so that we can avoid the effect of mediation from crisis managers and media experts hired to make them look less bad. Truth about this kind of character is larger than facts and investigative journalism can have a stronger impact if we incorporate it in the building of our narratives. If we leave the chance to meet them for last, we risk losing that — and also losing the fun of doing it,” he says.